When Your Discount Becomes Your Price

My daughter sat down at the dining room table where I was working and announced, “I can’t decide whether I should buy the AirPods at $89 or wait for them to drop lower.”

With a house full of teenagers and young adults, I’m used to having to dole out advice on “adulting”, but what struck me most about this question was not my daughter’s buying decision but that something serious had gone wrong in the pricing department of one of the world’s biggest and most successful companies.

Discounting can be a powerful tool for either taking a number of hesitant, potential customers and converting them into sales today or for reaching customers who are not quite willing to pay your normal prices but would be willing to pay a somewhat lower price.

However, discounts can also destroy the value of your product in your customers’ eyes and create a situation where customers are unwilling to buy your product at full price or even delay making a purchase at one discounted price because they believe there will be a lower discounted price soon.

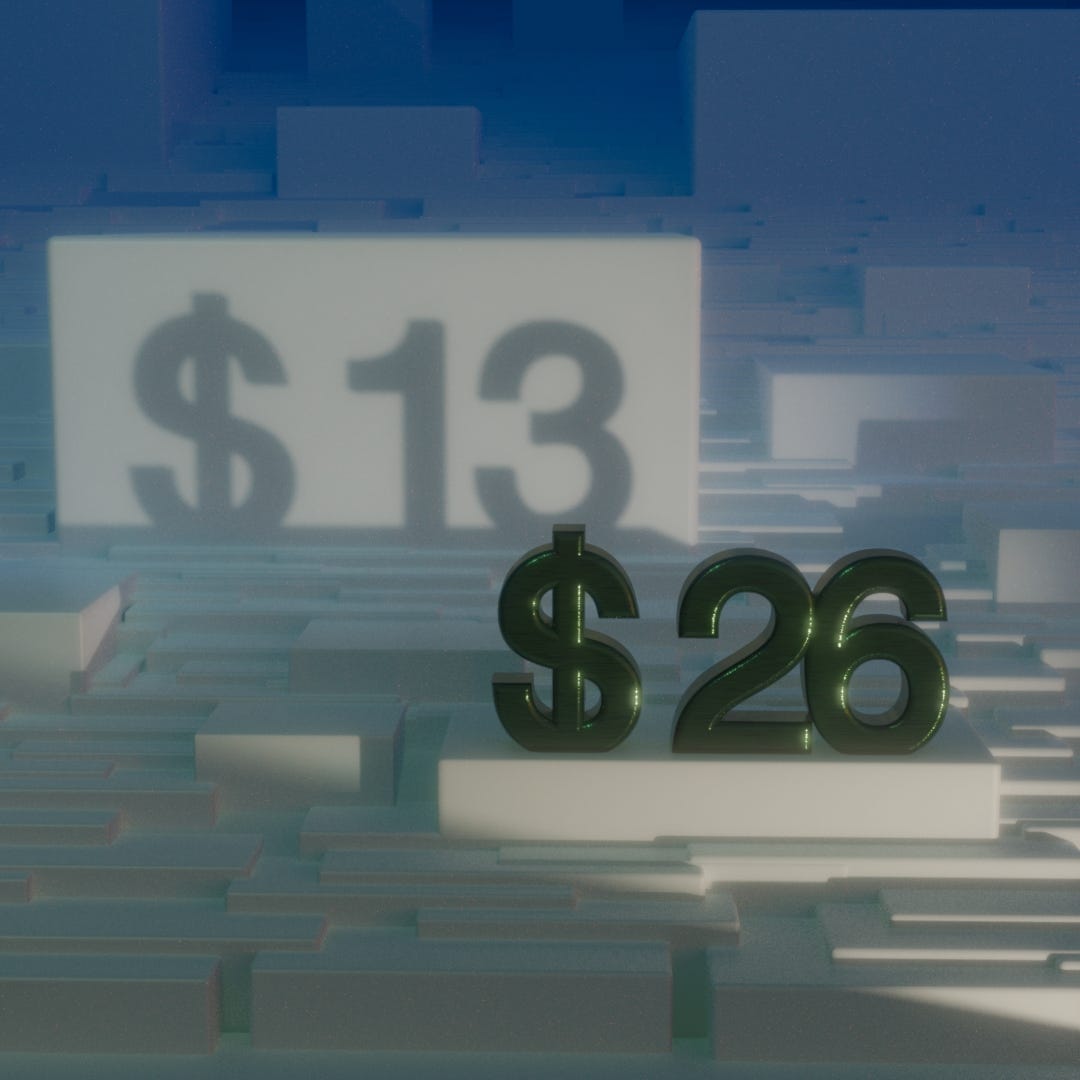

The first of those problems happens when regular and prominent discounting results in what we call “shadow pricing”.

A prominent example of shadow pricing is when a brand conducts regular sales which result in customers re-setting their expectations of the “right” price to pay for a product.

For example, for many years I was a loyal buyer of Brooks Brothers non-iron dress shirts. Their theoretical list price was about $99 per shirt. However, four or five times a year they would hold sales when you could buy them at 4-for-$200 ($50 each.) The fact that I knew I could regularly buy them for $50 each made me very reluctant to ever pay the higher price. I would wait for the sale. And many other customers must have been the same, because their sales became more frequent and deeper — right up until Brooks Brothers went through bankruptcy in the summer of 2020. Since then, they’ve been trying to build their pricing back up, but once you’ve trained your customers to buy only on sale (and you’ve decreased your quality in order to fit the product to the prices your customers are willing to pay) you’ve begun a long term slide out of which it’s very hard to escape.

If the danger with shadow pricing is that customers no longer consider your list price to be a real one, the other danger with discounting is instead of your discount strategy causing customers to hurry up and buy, it instead encourages your customers to wait for a better deal.

This is one aspect of the “shadow pricing” trap. Brooks Brothers, with their heavily publicized and regular discounting of around 50% off regular price, created a situation in which customers would delay their purchases till the next sale.

But when sale prices are progressively getting lower over time, or when you announce a major discount ahead of time, you may cause your customers to delay purchases in order to wait for a better price.

This is what my daughter was doing. And she was right. Because a few days later, Amazon dropped the price on the AirPods to $79. Now she’s wondering if it will get any lower by Black Friday or Cyber Monday.

Nor is the discount discretion which Apple is allowing its resellers like Amazon at the moment the only problem. I myself have been waiting to replace my old set of AirPod Pros. Those are currently marked down from $249 to $219 on Amazon, but on the Apple website, there are banners telling users that starting on November 28th, you can get a $50 apple gift card if you buy the AirPod Pros there.

In other words, their published discount strategy is telling you that you should not buy right now.

This is not what a discount strategy is supposed to do.

How should you avoid this trap?

Discounts should be used sparingly, they should not be too deep, and you should very clearly communicate when you are offering a “lowest price of the year” kind of sale.

Sparingly: For the kind of purchase which people might plan ahead of time, I would recommend that you not have a deep discount more than twice a year. You might have a smaller sale one or two times, but if you put a product on sale 4+ times a year, you are going to convince people that the full price is not the real price. Also, those sales should feel like they are short. Don’t advertise them for weeks ahead of time lest you cause people to delay their purchase. If most of the communication your customers hear from you is about sales, they will expect to buy your products on sale. Plan to have 75% or more of your communication be about your company, new products, value, etc. and at most 25% of your communication about sales.

Not too deep: The deeper the discount, the less relevant your everyday price seems. A 50% discount is so deep it makes customers think they are being ripped off paying the full price. There’s not a firm rule, but if you want to continue to sell most of your products at full price, I would recommend that you not discount deeper than 20% to 25%.

Clear communication: Don’t make your customers guess when the deepest sale is coming or how long it will last. Tell your customers when it’s the deepest discount of the year and how long they will have to act. This will achieve the goal of a promotion: converting the largest possible number of price-driven potential customers into actual buyers within a short time. The last thing you want to do when you’re already taking the brand risk of running a deep discount is to have some of your potential customers sit it out because they think a better deal may be coming soon.

Historically, Apple has had some of the greatest price discipline of the major brands. I’m not sure why they’re letting these things happen this year, but it doesn’t seem like an encouraging set of choices. However, I will probably replace that old pair of AirPod Pros come November 28th.

What do you think about companies like Land's End? Not only are you a fool to ever pay full price, they usually have competing discount codes so you can rebuild your cart until you have the best discount.