Good, Better, Best

Product line positioning which guides customer choice

From software service levels to products on store shelves, you’ve probably noticed how often you see products differentiated into three levels of quality — and price.

Good, Better, Best. Bronze, Silver, Gold. Different companies and industries apply different names to the approach, but the three-way split is the same. Why is this so common?

It turns out that this common approach is driven by insights into both how customers respond to choices and how they respond to pricing. Offering three options in a Good, Better, Best configuration often helps people make a decision faster and be willing to select a more expensive option.

If you haven’t already, you may want to consider your own product portfolio through this lens.

People like choices, but if they are confronted with too many choices, they may decide to wait till later before making a decision.

If you want your customer to make a decision quickly about which of your products to select, it can help if you arrange your product line into a limited range of distinct choices which it’s easy for the customer to pick from.

Three turns out to be a very useful configuration.

If you’re differentiating a specific type of product (as with the water bottle example which Ideogram helpfully provided for us above) you want your “good” option to provide just the basics. This is the choice for people who want this type of product but want the minimum price for the minimum frills. With this water bottle example, this is just a plastic bottle with a lid. Its function is: it holds water.

Your middle option should be the one which is suitable for the majority of customers at the price you want to get most of the time. For most product categories, this middle option is likely to be your highest seller. So, this should be a significantly better product that the “good” product, at a significantly higher price. How much higher will depend on your type of product, but it should be pretty clearly differentiated. For many products 20% to 30% more expensive is a good level of differentiation, but for low price points it might be up to twice the price of the basic option.

For the best option, you should provide the additional features which customers who think of themselves as wanting “the best” would desire. Your price should also be solidly more than the middle option. After all, if the customer is scared away by the price, they can always fall back on the middle option. Make your premium customers pay a premium price. Not only should you make the highest margin dollars for each unit sold at this level, but you should make it the highest margin rate as well.

This is not just a matter of greed. Making that top price high has an important function. It is an “anchor price”. This means that it sets the customer’s expectations of how high a price can be. One of the purposes of this product is to make the middle option seem affordable by comparison.

Many of us do not want to be seen as the sort of person who would blow money on the most expensive option. We want to think of ourselves as the sort of consumer who carefully weighs the different options and then makes the reasonable choice.

Therefore, if you give us just two options, one basic and one premium, we will tend to pick the basic option. But if you offer three options, the most premium option becomes the luxury option, while the middle option is the one for sensible people focused on value and the bottom option is just for cheapskates.

A price which might have seemed a bit on the high side can become normal if you throw in a very high price for comparison. That high price says, “See, some people are willing to spend this much for a really premium product.” And even if you are not one of those people, the comparison makes the others seem more normal.

That is why the high price is called an “anchor price”, it sets the customer’s expectations of how high a price could be.

Often you’ll hear a salesman throw out an anchor price as part of the sales process in order to make the one he eventually quotes you sound more reasonable. “Well, the manufacturer would like us to sell this car for $49,999, but right now we’ve got a dealer special where you can drive it off the lot for just $42,500.”

This can apply to all sorts of products. A while back, someone working with a non-profit asked me about what levels of support they should ask for in their pledge drive. They had planned to ask for $50/month or $100/month but wondered if they should ask for a higher level as well or if that would sound greedy. I suggested they throw in one more level at a significantly higher level such as $250/month. Probably not many people would pick that level, I said, but they might well get more people to pick the $100/month level if it wasn’t the very highest option. Putting that large amount out there makes donors realize that some people are willing to give that much.

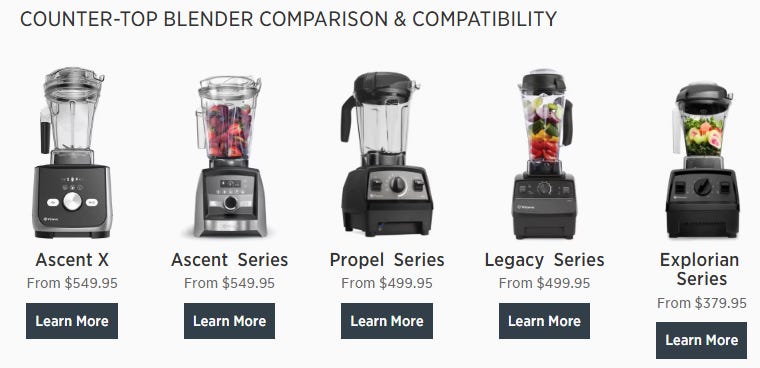

It’s important that your products really are differentiated by price to make this kind of strategy work. For instance, I’ve been in the market for a new blender lately. We use our blender quite a bit, and some people have told me that (having worn out a succession of KitchenAid blenders) we should try a Vitamix blender. But here’s the product lineup from their website:

Maybe I’m overly formed by languages that read from left to right, but I think that putting your Best option first and your Good option last is not a great call.

Second, they have five different product lines. Not totally excessive, but definitely a bit cluttered.

But the big issue is, their top two product lines (Ascent X and Ascent) are priced exactly the same. And those two are in turn priced only 10% above the next two product lines, (Propel and Legacy) which are priced exactly the same.

The Propel and Legacy product lines are 30% above the Exploration line, so it’s clear that the Exploration line is supposed to be the more basic while the Propel and Legacy are supposed to be the mid lines.

But Ascent is not priced like a premium line. And what am I supposed to make of two different product lines priced exactly the same in the middle of the lineup? Should I pick Propel or Legacy?

I’m sure that Vitamix makes a good blender, but their price positioning could use a little work.

How should you apply this to your own product lines?

Make sure that within a given functional product type, you have clear value positioning. This only applies to products which are directly comparable.

Vitamix, for instance, also sells food processors and immersion blenders. They don’t need to worry about how the price of a food processer compares with a blender. Those are different products which you want for different reasons.

But within a set of products which a customer might be reasonably choosing between to fulfill one function, you should provide them with a narrow range of choices with significantly different prices.

Within each of those choices, you might provide both value neutral options (for instance, different colors of water bottle or blender base) and also value driven options which are their own good, better, best options.

Think, for instance, of how within the range of iPhones you can pick first between an iPhone SE, 14, 15, or 16, and then within each of those product lines you will have choice of color (no price difference) but also screen size and amount of storage (which have significant price differences.)

The beauty of Good, Better, Best, is that you can nest one product line-up within another. It’s a great way of differentiating product each time you offer your customer a choice.

Even though I'm not a business person, I like reading about how a customer's mind works. I was particularly struck by the observation that too many choices can cause a person to delay choosing. In my case, it can cause me to leave a store! I think that's why I like to shop at Aldi. Fewer choices makes shopping more streamlined.